Team:TAS Taipei/modeling

From 2014hs.igem.org

Xiaoyangkao2 (Talk | contribs) |

Xiaoyangkao2 (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 324: | Line 324: | ||

<h4>Self-Repressilator</h4> | <h4>Self-Repressilator</h4> | ||

<p>We first attempted to model the self-repressilator, which we know was an early design. The self-repressilator is significant because it lays the groundwork for the model of the two-component oscillator, which is really an expansion on the self-repressilator. The groundwork includes establishing the need for an explicit time delay, which is elaborated in the paper “Design Principles of Biochemical Oscillators†by Novak and Tyson. In this model, transcription is based on protein concentration in a previous point in time, to compensate for the time delay in transcription and translation. The explicit time delay was not needed in the three component oscillator because it established a time delay through a series of intermediates. The equations are as follows:</p> | <p>We first attempted to model the self-repressilator, which we know was an early design. The self-repressilator is significant because it lays the groundwork for the model of the two-component oscillator, which is really an expansion on the self-repressilator. The groundwork includes establishing the need for an explicit time delay, which is elaborated in the paper “Design Principles of Biochemical Oscillators†by Novak and Tyson. In this model, transcription is based on protein concentration in a previous point in time, to compensate for the time delay in transcription and translation. The explicit time delay was not needed in the three component oscillator because it established a time delay through a series of intermediates. The equations are as follows:</p> | ||

| - | <img src="https:// | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014hs/7/76/Image13.png"> |

<p>Without the explicit time delay, the graph would look like this, which we know that it shouldn’t look like:</p> | <p>Without the explicit time delay, the graph would look like this, which we know that it shouldn’t look like:</p> | ||

<figure style='width:600px;margin-top:10px;'> | <figure style='width:600px;margin-top:10px;'> | ||

| - | <img src='https:// | + | <img src='https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014hs/2/23/Image20.jpg'> |

<figcaption class='darkblue'>Figure 7: Graph showing the relationship between time and LacI concentration. The system tends to equilibrium quickly without an explicit time delay in the equations.</figcaption> | <figcaption class='darkblue'>Figure 7: Graph showing the relationship between time and LacI concentration. The system tends to equilibrium quickly without an explicit time delay in the equations.</figcaption> | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

Revision as of 08:26, 19 July 2014

Modeling

The aim of modeling in our project is to try to simulate the interactions between the different parts of our project: telomere extension, circuit regulation, and safety. In telomere extension, we mapped out the induction of the hTERT promoter by c-Myc and used that to quantify the minimum number of c-Myc molecules needed to maintain telomeres. In circuit regulation, we simulated the behaviors of different oscillator designs and compared their attributes to help decide on our construct. Finally, in safety termination, we constructed a qualitative analysis of means by which our construct ensures safety. Through the predicted results with certain parameters, modeling can be used to guide the direction of the project and determine what tweaks should be made to achieve our goal. We graphed all the models using numerical integration in Wolfram Mathematica.

General Format for Equations

For our project, we are modeling the rate of change in the number of proteins. This is dependent on translation of mRNA and the degradation rate of the proteins.

The amount of mRNA depends on the activity of the promoter transcribing the mRNA and the degradation rate of the mRNA. Promoter activity is described by the Hill equation, which can describe the effect of activation or repression by a transcription factor.

General Concepts

The maximum promoter strength, denoted by B, describes the rate of mRNA transcription and is listed in units of mRNA transcripts/min. The dissociation constant(Kd) describes the tendency of the transcription factor to separate into its subunits. Kd describes the binding affinity between the proteins and their target promoters. A higher Kd would mean that the protein has a hard time binding correctly to the promoter and a lower Kd would mean that it is comparatively easier for the protein to bind to its target promoter. Biologically, the Kd describes the concentration at which the promoter is 50% occupied. Lastly, the cooperativity, which is represented by n, describes the extent to which transcription factor binding will increase the attraction of the binding site to other transcription factors. A higher cooperativity would mean that binding of the regulating protein greatly increases the affinity of other regulators to bind. On a graph, that would mean that the system resembles a switch, showing a rapid change in state with a small difference in protein concentration.

Telomere Extension

Quantifying telomerase expression

The goal of our project is to minimally express telomerase so that the target cell can maintain their telomeres. Each telomerase molecule acts on one telomere during the cell cycle during the S phase under telomere-maintaining conditions. For the purposes of our project, we are unable to take into account all the other factors that influence telomere shortening and elongation, so we only focus on the amount of telomerase molecules needed to elongate telomeres. Since we are aiming to ultimately have this apply to humans, an absolute minimum of 92 molecules of telomerase would be needed per cell, since there are 23 pairs of chromosomes and four telomeres for every pair. However, chromosomes are located in the nucleus, which takes up only about 10% of the cell volume. We have no method of transport in our project, so instead we aim to express ten times more telomerase to compensate, as it is extremely unlikely that all telomerase molecules will be in contact with telomeres. Thus, the telomere extension portion of our project focuses on trying to achieve keep around 920 molecules of telomerase in every cell.

Determining c-Myc induction of hTERT

The first step of telomere extension was determining the relationship between our regulator of telomerase, c-Myc, and telomerase transcription by the hTERT promoter. c-Myc is able to bind to binding sites on the hTERT promoter that then stimulate transcription. We treated hTERT and telomerase as the same even though hTERT is only a subunit of telomerase, as papers have shown that hTERT is the rate-limiting component of telomerase and that hTERT and telomerase activity correlate with each other. We consulted a paper on c-Myc and hTERT and curve-fitted it using the form of the Hill equation that describes the kinetics of the reaction. However, before doing this, we made the conversions shown below to convert the concentration of c-Myc from ug/well to proteins/cell to simplify comparisons:

The molecular weight of c-Myc was listed at 67kDa. We took the average volume of a mammalian cell, which can be anywhere from 500 to 5000 um3. The Zou et. al. paper cited that they used a standard 6-well plate, which is usually 5 mL in volume but cells grew to about 70 or 80% confluence, so we used this information to calculate the number of cells at 2750 um3 that would add up to 5*0.8 mL in volume.

The results of the conversions are shown in the following table:

| ug/well | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecules/cell | 3088.619402 | 6177.238804 | 9265.858206 | 12354.47761. |

The translation of hTERT depends on the amount of hTERT mRNA, which is in turn governed by the activity of the hTERT promoter. hTERT is induced by c-Myc, so the following equation was used: B*xn/(Kd+xn). B stands for the maximum promoter activity, in transcripts/min; n represents the cooperativity, meaning the amount that binding of c-Myc increases binding affinity; Kd is the dissociation constant, which describes how readily a substance separates into components; x stands for the amount of c-Myc at a certain point in time. However, since the y-axis of the graph given in the Zou et. al. paper measured relative fluorescence, the value of B actually did not mean a lot. Without information on absolute promoter strength in transcripts/min after sifting through literature and failing to acquire the hTERT promoter, we just assumed that it had the same value as the promoters given in the Elowitz paper at 29.97 transcripts/min. After completing this curve-fit, we were able to map out the regulation of hTERT and telomerase by combining this data with their half-lives.

General form of equations:

Equations with values:

At this point, telomere extension is dependent on circuit regulation because c-Myc is regulated by the oscillator. The exact tweaks will be discussed in the next section, but here a graph of optimal results is shown after altering LacI and hTERT half-life by a factor of five with an ssRA tag:

Circuit Regulation

The circuit regulation section of modeling focuses on simulating the oscillating constructs that we came up with and approximating their behavior in real life. To oscillate, a system must have a balance between promoter strength and repressor half-life[12]. In addition, a time delay of a sort, whether through a series of intermediates or through implementation of an explicit time delay in the model, is needed.[13] Finally, the pattern of regulation must be sufficiently nonlinear(high cooperativity) for there to be oscillations.

Three-component oscillator

The three component oscillator features three promoters that repress each other. With modeling, we first used the values showcased in Elowitz’s paper from the BioModels databse on the repressilator and showed that the resulting system oscillated with the following equations and parameters:

However, the paper assumed that every parameter for every part was the same, so we decided to explore what would happen if we changed things around. We identified promoter strength, dissociation constant, and protein half-lives as possible factors that could change the behavior of the system, so we thus made some changes and observed what would happen to the systems.

Testing

Purpose: The promoter strength, repressor half-lives, and dissociation constants were all assumed to be the same in models of the three component oscillator. However, we found evidence that promoter strengths, dissociation constants, and repressor half lives for components in the oscillator are different. We thus decided to test if differences in these parameters changed oscillator behavior.

Promoter Strength Test

Repressor Half-Life Test

Dissociation Constant Test

Combined Test

Results

Changing the promoter strength simply changed the peaks of the proteins and had little effect on derailing the oscillation. On the other hand, changing the half-lives and dissociation constants had profound effects on oscillator behavior. After making LacI half-life five times as long, the oscillations dampened quickly and the system tended towards equilibrium. The oscillator did show some resistance to reducing half-lives, but overall it showed that differences in protein half-life can completely derail the oscillations. Changing the dissociation constant to the more realistic estimates computed by the 2009 Aberdeen iGEM team had an even more profound effect; the system immediately tended towards equilibrium, as more repressors were needed to overcome the effect of dissociation.

Conclusion

Our experience with the three component oscillator showed that it was a plausible approach towards expressing c-Myc, but we were afraid of its applicability in real life. After all, the model presented by Elowitz and Leibler was based on ideal values that had a high probability to be different in real life. We thus explored other designs that were better suited for our project.

Alternatives to the three component oscillator

Self-Repressilator

We first attempted to model the self-repressilator, which we know was an early design. The self-repressilator is significant because it lays the groundwork for the model of the two-component oscillator, which is really an expansion on the self-repressilator. The groundwork includes establishing the need for an explicit time delay, which is elaborated in the paper “Design Principles of Biochemical Oscillators†by Novak and Tyson. In this model, transcription is based on protein concentration in a previous point in time, to compensate for the time delay in transcription and translation. The explicit time delay was not needed in the three component oscillator because it established a time delay through a series of intermediates. The equations are as follows:

Without the explicit time delay, the graph would look like this, which we know that it shouldn’t look like:

We thus implemented the time delay, along with a change to LacI half-life to make the system oscillate:

Two Component Oscillator

As shown above, two component oscillator is an expanded version of the self-repressilator. The pLac-LacI sequence was already shown to oscillate in the self-repressilator above. Thus, TetR/RFP, which is expressed by pLac, will also oscillate. This means that expression of c-Myc will be oscillatory, because pTet is regulated by TetR. For experimental purposes, GFP took the place of c-Myc as a reporter to show oscillations.

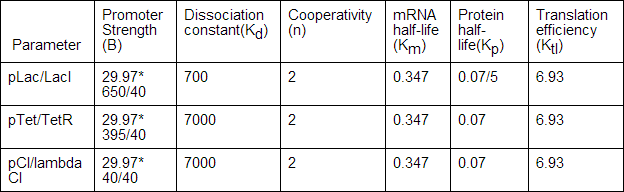

The parameters that were used to construct the two component oscillator model were taken from a variety of sources. The promoter strengths were adjusted according to the ratios found by Drew Endy and other researchers, at a ratio of 650:395:40.[18] The repressor half-life of LacI was adjusted to be shorter, based on the self-repressilator. In reality, this can be done by the application of ssrA tags, which can decrease the half-life of proteins.[19] Finally, the dissociation constants of each protein and the cooperativity of TetR were altered based on the findings of the 2009 Aberdeen iGEM team.[20] They found that the values of Kd(dissociation constant) cited in papers were too low because they conducted experiments in vitro instead of in vivo. Those experiments also did not take into account non-specific binding. The dissociation constants for LacI, TetR, and lambda CI were then estimated to be 700,7000, and 7000, respectively.[21] Cooperativity of TetR was also found to be three instead of two.[22]

The two component oscillator is significant for two main reasons. First, its basis on pLac and LacI allows synchronization through the use of IPTG, making it easier for oscillations to actually bet tested. In addition, the system oscillated with the usage of more realistic parameters, contrary to the three component oscillator that tended towards equilibrium. These characteristics are shown in the graphs below:

Conclusion

Overall, the two component oscillator has a simpler design and is thus less constrained by differences of promoter strength, repressor half lives, and repressor dissociation constants. This makes the two component oscillator more realistically implementable. The oscillator also has an added benefit of easy synchronization with IPTG. Finally, after adjusting the parameters based on literature and tweaking LacI half-life with an ssrA tag, we were able to express the number of c-Myc proteins necessary to maintain telomere length.

Safety Termination

For the safety termination portion of our circuit, we express BRCA1 and Apoptin behind pSurvivin, which is a tumor-specific promoter.[23] We were unable to produce a definite model that featured quantitative analysis, but were able to map out the mechanism for the safety mechanism. Apoptin induces apoptosis only in cancer cells, thus eliminating threat of metastasis.[24] The wtBRCA1 protein product has been shown to interact with c-Myc.[25] From the literature we have read, it seems to inhibit the hTERT promoter in multiple ways. BRCA1 has been shown to bind to c-Myc partially and inhibit its transcriptional and transformational activity in cells. BRCA1 is also suggested to inhibit hTERT promoter activity by binding to it.[26][27] Thus, we have been able to piece together the following mechanism:

Citations

[1] Zhao, Yong, Eladio Abreu, Jinyong Kim, Guido Stadler, Ugur Eskiocak, Michael P. Terns, Rebecca M. Terns, Jerry W. Shay, and Woodring E. Wright. "Processive and Distributive Extension of Human Telomeres by Telomerase under Homeostatic and Nonequilibrium Conditions." Molecular Cell, no. 42 (May 6, 2011): 297-307.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Harvard. "Key Numbers for Cell Biologists." B10NUMB3R5. http://www.google.com/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Fbionumbers.hms.harvard.edu%2FIncludes%2FKeyNumbersLinks.pdf&sa=D&sntz=1&usg=AFQjCNFyHaFJOqgspkVAHVMiHzUTU5Ky9A.

[4] Oh, Stephen T., Saturo Kyo, and Laimonis A. Laimins. "Telomerase Activation by Human Papillomavirus Type 16 E6 Protein: Induction of Human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Expression through Myc and GC-Rich Sp1 Binding Sites." Journal of Virology 75, no. 12 (June 2001): 5559-66

[5] Poole, Joseph C., Lucy G. Andrews, and Trygve O. Tollefsbol. "Activity, Function, and Gene Regulation of the Catalytic Subunit of Telomerase (hTERT)." Gene 269, nos. 1-2 (May 16, 2001): 1-12.

[6] Zou, Lin, Peng-Hui Zhang, Chun-Li Luo, and Zhi-Guang Tu. "Transcript Regulation of Human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase by C-myc and Mad1." Acta Biochimica Et Biophysica Sinica 37, no. 1 (January 2005): 32-38.

[7] Harvard. "Key Numbers for Cell Biologists." B10NUMB3R5. http://www.google.com/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Fbionumbers.hms.harvard.edu%2FIncludes%2FKeyNumbersLinks.pdf&sa=D&sntz=1&usg=AFQjCNFyHaFJOqgspkVAHVMiHzUTU5Ky9A.

[8] Ibid

[9] Kapeli, Katannya, and Peter J. Hurlin. "Differential Regulation of N-Myc and c-Myc Synthesis, Degradation, and Transcriptional Activity by the Ras/Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Pathway." The Journal of Biological Chemistry, no. 286 (September 9, 2011): 38498-508.

[10] Chai, Juin Hsien, Yong Zhang, Wei Han Tan, Wee Joo Chng, Baojie Li, and Xueying Wang. "Supplemental Data Regulation of hTert by BCR-ABL at Multiple Levels in K562 Cells." BioMed Central. http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/supplementary/1471-2407-11-512-s1.pdf.

[11] Purcell, Oliver, Claire S. Grierson, Mario di Bernardo, and Nigel J. Savery. "Temperature dependence of ssrA-tag mediated protein degradation." Journal of Biological Engineering 6, no. 10 (July 23, 2012).

[12] Elowitz, Michael B., and Stanislas Leibler. "A Synthetic Oscillatory Network of Transcriptional Regulators." Nature 403 (January 20, 2000): 335-38.

[13] Novák, Béla, and John J. Tyson. "Design Principles of Biochemical Oscillators." Nature Reviews, Molecular Cell Biology ser., 9 (December 2008): 981-91.

[14] Ibid

[15] Elowitz, Michael B., and Stanislas Leibler. "Repressilator." Unpublished manuscript, Princeton University, January 20, 2000. http://www.google.com/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ebi.ac.uk%2Fbiomodels-main%2FBIOMD0000000012&sa=D&sntz=1&usg=AFQjCNGFLiZJXYrJcIBwjChGavz6UcD-LQ.

[16] Novák, Béla, and John J. Tyson. "Design Principles of Biochemical Oscillators." Nature Reviews, Molecular Cell Biology ser., 9 (December 2008): 981-91.

[17] Novák, Béla, and John J. Tyson. "Design Principles of Biochemical Oscillators." Nature Reviews, Molecular Cell Biology ser., 9 (December 2008): 981-91.

[18] Endy, Drew E., J. C. Conboy, and C. C. Braff. "Promoter Characterization Experiments." Last modified April 22, 2008. Microsoft Word.

[19] Purcell, Oliver, Claire S. Grierson, Mario di Bernardo, and Nigel J. Savery. "Temperature dependence of ssrA-tag mediated protein degradation." Journal of Biological Engineering 6, no. 10 (July 23, 2012).

[20] "Parameters." Team:Aberdeen_Scotland. http://www.google.com/url?q=http%3A%2F%2F2009.igem.org%2FTeam%3AAberdeen_Scotland%2Fparameters&sa=D&sntz=1&usg=AFQjCNG77BKYa2vSFwumEYhS6s_jWMAEKQ.

[21] Ibid

[22] Ibid

[23] Yang, L., Z. Cao, F. Li, D. E. Post, E. G. Van Meir, H. Zhong, and W. C. Wood. "Tumor-specific Gene Expression Using the Survivin Promoter Is Further Increased by Hypoxia." Gene Therapy, no. 11 (2004): 1215-33.

[24] Sun Yat-Sen University. "Project/Design." iPS Cells Safeguard. Last modified

2013.https://2013.igem.org/Team:SYSU-China/Project/Design.

[25] Blagosklonny, Mikhail V., Won G. An, Giovanni Melillo, Phuongmai Nguyen, Jane B. Trepel, and Leonard M. Neckers. "Regulation of BRCA1 by Protein Degradation." Oncogene 18, no. 47 (November 11, 1999): 6460-68.

[26] Blagosklonny, Mikhail V., Won G. An, Giovanni Melillo, Phuongmai Nguyen, Jane B. Trepel, and Leonard M. Neckers. "Regulation of BRCA1 by Protein Degradation." Oncogene 18, no. 47 (November 11, 1999): 6460-68.

[27] Xiong, Jingbo, Saijun Fan, Qinghui Meng, Laura Schramm, Chenguang Wang, Boumedienne Bouzahza, Jinnian Zhou, Brian Zafonte, Itzhak D. Goldberg, Bassem R. Haddad, Richard G. Pestell, and Eliot M. Rosen. "BRCA1 Inhibition of Telomerase Activity in Cultured Cells."Molecular and Cellular Biology 23, no. 23 (December 2003): 8668-90

"

"